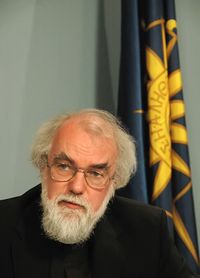

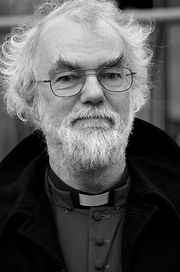

Rowan Williams

| The Most Revd and Rt Hon[1] Rowan Williams FRSL FBA |

|

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

|

|

| Province | Province of Canterbury |

| Diocese | Diocese of Canterbury |

| Enthroned | 27 February 2003 |

| Predecessor | George Carey |

| Other posts | Bishop of Monmouth (1992–2002) Archbishop of Wales (2000–2002) |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1977[1] |

| Consecration | 1 May 1992[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Rowan Douglas Williams |

| Born | 14 June 1950 Swansea, Wales |

| Nationality | Welsh |

| Denomination | Anglicanism |

| Residence | Lambeth Palace, London Old Palace, Canterbury |

| Parents | Aneurin Williams & Dolphine Morris |

| Spouse | Jane Paul (1981—) |

| Children | 1 son, 1 daughter |

| Profession | Theologian |

| Alma mater | Christ's College, Cambridge Wadham College, Oxford |

| Signature | |

Rowan Douglas Williams, FRSL, FBA (born 14 June 1950) is an Anglican bishop, poet, and theologian. He is the current (104th) Archbishop of Canterbury, Metropolitan of the Province of Canterbury and Primate of All England, offices he has held since early 2003.

Williams was previously Bishop of Monmouth and Archbishop of Wales (making him the first Archbishop of Canterbury in modern times not to be appointed from within the Church of England) and had spent much of his earlier career as an academic at the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford successively. His primacy has been marked by much speculation that the Anglican Communion (in which the Archbishop of Canterbury is the leading figure) is on the verge of fragmentation and by Williams's attempts to keep all sides talking to one another.

Life and career

Early life and ordination

Williams was born on 14 June 1950 in Ystradgynlais, Swansea, Wales, into a Welsh-speaking family. He was the only child of Aneurin Williams and Dolphine (Del, Nancy) Morris - Presbyterians who converted to Anglicanism in 1961. He was educated at the state school Dynevor School in Swansea, at Christ's College, Cambridge, where he studied theology, and at Wadham College, Oxford, where he took his DPhil in 1975.

He lectured at the College of the Resurrection in Mirfield, West Yorkshire for two years. In 1977 he returned to Cambridge to teach theology, first at Westcott House, having been ordained deacon in Ely Cathedral that year and was ordained priest in 1978.

Professor and pastor

Unusually, he undertook no formal curacy until 1980 when he served at St George's Chesterton until 1983, having been appointed as a lecturer in divinity at the University of Cambridge. In 1984 he became dean and chaplain of Clare College, Cambridge and, in 1986, at the very young age of 36, he was appointed to the Lady Margaret Professorship of Divinity at the University of Oxford and thus also a residentiary canon of Christ Church. He was awarded the degree of Doctor of Divinity in 1989.

Bishop

In 1991 Williams was appointed and consecrated Bishop of Monmouth in the Church in Wales. He continued in his post as Bishop of Monmouth and in 1999 he was elected Archbishop of Wales. In 2002 he was announced as the successor to George Carey as Archbishop of Canterbury - the senior bishop in the Church of England - and primus inter pares of the bishops of the Anglican Communion. As a bishop of the disestablished Church in Wales, Williams was the first Archbishop of Canterbury since the English Reformation to be appointed from a position outside the Church of England. He was enthroned on 27 February 2003 as the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury.

Since he became a bishop several institutions have granted him honorary degrees and fellowships, such as Kent, Cambridge, Oxford and Roehampton universities.

In 2005 he was inaugurated as the first Chancellor of Canterbury Christ Church University. This was in addition to his ex officio role as Visitor at King's College London, the University of Kent and Keble College, Oxford. The University of Cambridge awarded him an honorary Doctorate in Divinity in 2006.[2] In April 2007, Trinity College and Wycliffe College, both associated with the University of Toronto, awarded him a joint Doctor of Divinity degree during his first visit to Canada since being enthroned.

Williams is a noted poet and translator of poetry. His collection The Poems of Rowan Williams, published by Perpetua Press, was longlisted for the Wales Book of the Year award in 2004. Beside his own poems, which have a strong spiritual and landscape flavour, the collection contains several fluent translations from Welsh poets. He got into trouble with the press for allegedly supporting a 'pagan organisation', the Welsh Gorsedd of Bards, which promotes Welsh language and literature and uses druidic ceremonial but is actually not religious in nature.[3] His wife, Jane Williams, is a writer and lecturer in theology. They married in 1981 and have two children.

Williams' summer residence is in the Oxfordshire town of Charlbury and when resident on Sundays he worships at the local church.

Traditionally, as Archbishop of Canterbury, Williams acts as a governor of Charterhouse School. He is patron of the Canterbury Open Centre run by Catching Lives, a local charity supporting the destitute.[4]

Williams is also patron of the Peace Mala Youth Project For World Peace since 2002, and led the ceremony that launched the charity as one of his last engagements as Archbishop of Wales.[5]

He speaks or reads 11 languages: English, Welsh, Spanish, French, German, Russian, Biblical Hebrew, Syriac, Latin and both Ancient (koine) and Modern Greek.[6][7] He learnt Russian in order to be able to read the works of Dostoevsky in the original.[8]

Archbishop of Canterbury

Also see Leaders of Christianity

Williams' appointment to Canterbury was widely predicted. A churchman who had demonstrated a huge range of interests in social and political matters, he was widely regarded, by academics and others, as a figure who could make Christianity credible to the intelligent unbeliever. As a patron of Affirming Catholicism his appointment was a considerable departure from that of his predecessor and his views (not least those expressed in a widely published lecture on homosexuality (see below)) were seized on by a number of Evangelical and conservative Anglicans. The issue had begun to divide the communion, however, and the archbishop, in his position as nominal head of the Anglican Communion, would be bound to have an important role.

Views

Theological views

He is a scholar of the Church Fathers as well as a historian of Christian spirituality.

In 1983 he wrote that orthodoxy should be seen "as a tool rather than an end in itself..." It is not something which stands still. Thus "old styles come under increasing strain, new speech needs to be generated".[9] He sees orthodoxy as a number of "dialogues": a constant dialogue with Christ, crucified and risen; but also that of the community of faith with the world - "a risky enterprise", as he writes. "We ought to be puzzled", he says, "when the world is not challenged by the gospel." It may mean that Christians have not understood the kinds of bondage to which the gospel is addressed.[10] He has also written that "orthodoxy is inseparable from sacramental practice... The eucharist is the paradigm of that dialogue which is 'orthodoxy'".[11] This stance may help to explain both his social radicalism and his view of the importance of the Church, and thus of the holding together of the Anglican communion over matters such as homosexuality: his belief in the idea of the Church is profound.

John Shelby Spong once accused Williams of being a 'neo-medievalist', preaching orthodoxy to the people in the pew but knowing in private that it is not true. In an interview with Third Way Magazine Williams responded: "I am genuinely a lot more conservative than he would like me to be. Take the Resurrection. I think he has said that of course I know what all the reputable scholars think on the subject and therefore when I talk about the risen body I must mean something other than the empty tomb. But I don't. I don't know how to persuade him, but I really don't."[12]

Although generally considered as an Anglo-Catholic, his sympathies are broad. One of his first publications was in the largely evangelical Grove Books series with the title Eucharistic Sacrifice: the Roots of a Metaphor.

Social views

His interest in and involvement with social issues is longstanding. Whilst chaplain of Clare College, Cambridge, Williams took part in anti-nuclear demonstrations at United States bases. In 1985, he was arrested for singing psalms as part of a protest organized by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament at Lakenheath, an American air base in Suffolk; his fine was paid by his college. At this time he was a member of the left-wing Anglo-Catholic Jubilee Group headed by Father Kenneth Leech and he collaborated with Leech in a number of publications including the anthology of essays to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Assize Sermon entitled Essays Catholic and Radical in 1983.

He was in New York at the time of the 11 September 2001 attacks, only yards from Ground Zero delivering a lecture; he subsequently wrote a short book, 'Writing in the Dust', offering reflections on the event. In reference to Al Qaeda, he claimed that terrorists "can have serious moral goals"[13] and that "Bombast about evil individuals doesn't help in understanding anything."[14] He has subsequently worked with Muslim leaders in England, and on the third anniversary of 9/11 spoke, by invitation, at the Al-Azhar University Institute in Cairo on the subject of the Trinity. He stated that the followers of the will of God should not be led into ways of violence. He contributed to the debate prior to the 2005 United Kingdom General Election criticising assertions that immigration was a cause of crime. Williams has argued that the partial adoption of Islamic Sharia law in the United Kingdom is "unavoidable" as a method of arbitration in such affairs as marriage, and should not be resisted.[15][16][17] On 15 November 2008, the Archbishop visited the Balaji Temple in Tividale, West Midlands, on a goodwill mission to represent the friendship between the two faiths of Christianity and Hinduism.[18]

Sharia law

Williams was the subject of a media and press furore in February 2008, following a lecture he gave to the Temple foundation at the Royal Courts of Justice[19] on the subject of 'Islam and English Law'. He raised the question of conflicting loyalties which communities might have, cultural, religious and civic and argued that theology has a place in debates about the very nature of law 'however hard our culture may try to keep it out' and noted that there is in a 'dominant human rights philosophy' a reluctance to acknowledge the liberty of conscientious objection. He spoke of 'supplementary jurisdictions' to that of the civil law.[20] Noting the anxieties which the word Sharia provoked in the West he drew attention to the fact that there was a debate within Islam between what he called "primitivists" for whom, for instance, apostasy should still be punishable and those Muslims who argued that Sharia was a developing system of Islamic jurisprudence that such a view was no longer acceptable. He made comparisons with "Orthodox Jewish practice" (Beth Din) and with the recognition of the exercise of conscience of Christians.[19]

His words were critically interpreted as proposing a parallel jurisdiction to the civil law for Muslims (Sharia), and was the subject of demands from elements of the press and media for his resignation.[21] He also attracted criticism from elements of the Anglican Communion.[22]

In response, Williams stated in a BBC interview "... certain provision[s] of Sharia are already recognised in our society and under our law; ... we already have in this country a number of situations in which the internal law of religious communities is recognised by the law of the land as justified conscientious objections in certain circumstances in providing certain kinds of social relations" and that "we have Orthodox Jewish courts operating in this country legally and in a regulated way because there are modes of dispute resolution and customary provisions which apply there in the light of Talmud."[23] Williams also denied accusations of proposing a parallel Islamic legal system within Britain.[22] Williams also acknowledged that Sharia, "In some of the ways it has been codified and practised across the world, it has been appalling and applied to women in places like Saudi Arabia, it is grim."[24]

On 4 July 2008 Sharia again became a topic of media interest, following comments by Lord Phillips, the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales. He supported the idea that Sharia could be reasonably employed as a basis for "mediation or other forms of alternative dispute resolution". He went further to defend Williams's position from earlier in the year, explaining "It was not very radical to advocate embracing sharia law in the context of family disputes, for example, and our system already goes a long way towards accommodating the archbishop's suggestion." and "It is possible in this country for those who are entering into a contractual agreement to agree that the agreement shall be governed by a law other than English law."[25]

Moral positions

Williams' contributions to Anglican views of homosexuality were perceived as quite liberal before he became the Archbishop of Canterbury. These views are evident in a paper written by Williams called 'The Body’s Grace',[26] which he originally delivered as the 10th Michael Harding Memorial Address in 1989 to the Lesbian and Gay Christian Movement, and which is now part of a series of essays collected in the book "Theology and Sexuality" (ed. Eugene Rogers, Blackwells 2002).

Free market

In 2002 he delivered the Richard Dimbleby lecture and chose to talk about the problematic nature of the nation-state but also of its successors. He cited the so-called 'market state' as offering an inadequate vision of the way a state should operate, partly because it was liable to short-term and narrowed concerns (thus rendering it incapable of dealing with, for instance, issues relating to the degradation of the natural environment) and partly because a public arena which had become value-free was liable to disappear amidst the multitude of competing private interests. (He noted the same moral vacuum in British society after this visit to China in 2006.) He is not uncritical of communitarianism, but his reservations about consumerism have been a constant theme. These views have often been expressed in quite strong terms; for example, he once commented that "Every transaction in the developed economies of the West can be interpreted as an act of aggression against the economic losers in the worldwide game."[27]

Creationism

His response to a controversy about the teaching of creationism in privately sponsored academies was that it should not be taught in schools as an alternative to evolution.[28] When asked if he was comfortable with teaching creationism, he said "I think creationism is, in a sense, a kind of category mistake, as if the Bible were a theory like other theories… so if creationism is presented as a stark alternative theory alongside other theories, I think there's - there's just been a jar of categories, it's not what it's about." When the interviewer said "So it shouldn't be taught?" he responded "I don't think it should, actually. No, no. And that's different from saying–different from discussing, teaching about what creation means. For that matter, it's not even the same as saying that Darwinism is–is the only thing that ought to be taught. My worry is creationism can end up reducing the doctrine of creation rather than enhancing it."[29]

In this, Williams has maintained traditional support amongst Anglicans and their leaders for the teaching of evolution as fully compatible with Christianity. This support has dated at least back to Frederick Temple's tenure as Archbishop of Canterbury.

Iraq War and possible attack on Syria or Iran

He was to repeat his opposition to American action in October 2002 when he signed a petition against the Iraq War as being against UN ethics and Christian teaching, and 'lowering the threshold of war unacceptably'. Again on 30 June 2004, together with the Archbishop of York, David Hope, and on behalf of all 114 Church of England bishops, he wrote to Tony Blair expressing deep concern about UK government policy and criticising the coalition troops' conduct in Iraq. The letter cited the abuse of Iraqi detainees, which was described as having been "deeply damaging" - and stated that the government's apparent double standards "diminish the credibility of western governments".[30][31] In December 2006 he expressed doubts in an interview on the Today programme on BBC Radio 4 about whether he had done enough to oppose the war.[32]

On October 5, 2007 Williams visited Iraqi refugees in Syria. In a BBC interview after his trip he described advocates of a US attack on Syria or Iran as "criminal, ignorant and potentially murderous."[33] A few days earlier, the former US ambassador to the UN, John Bolton had called for bombing of Iran at a fringe meeting of the Conservative Party conference.[34]

When people talk about further destabilization of the region and you read some American political advisers speaking of action against Syria and Iran, I can only say that I regard that as criminal, ignorant and potentially murderous folly.[35]– Rowan Williams, 5 October 2007

Opinion about hijab and terrorism

Dr. Rowan Williams voiced his objection toward the anticipated passing of a French law proposing a ban on the wearing of the hijab, a traditional Islamic headscarf for women, in the French schools which would imply fear of allowing people to openly demonstrate any kind of religious commitment. He condemned the proposal of such law and stated that the hijab and any other religious symbols should not be outlawed. [36]

Rowan Williams also raised his opinion about claims that the al-Qaeda were responsible for the terrorist attacks in the London underground trains and a bus, which killed 33 and wounded about 700. Four mosques in England were assaulted; Muslims were verbally insulted in streets; and Muslims' cars and houses were vandalized by publics expressing anti-Islamic sentiment. However, Rowan Williams expressed his worry over Muslims acting as scapegoats for the bombings. Rowan Williams strongly condemned the terrorist attacks and stated that they cannot be justified. However, he added that "any person can commit a crime in the name of religion and it is not particularly Islam to be blamed. Some persons committed deeds in the name of Islam but the deeds contradict Islamic belief and philosophy completely." Such statements show his refusal to place general blame on Muslims for such terrorist attacks. [37]

Interview with Emel magazine

In November 2007, Williams gave an interview for Emel magazine, a lifestyle magazine celebrating contemporary British Muslim culture.[38] Williams condemned the United States and certain Christian groups for their role in the Middle East, while his criticism of some trends within Islam went largely unreported. As reported by Times Online, he was greatly critical of the United States, the Iraq war, and Christian Zionists, yet made "only mild criticisms of the Islamic world".[39] He claimed "the United States wields its power in a way that is worse than Britain during its imperial heyday". He compared Muslims in Britain to the Good Samaritans, praised Muslim salah ritual of five prayers a day, but said in Muslim nations, the "present political solutions aren't always very impressive".

Ecumenism

Williams did his doctoral work on Vladimir Lossky, the famous Russian Orthodox theologian of the early-mid 20th century, and is currently patron of the Fellowship of Saint Alban and Saint Sergius,[40] an ecumenical forum for Orthodox and Western (primarily Anglican) Christians. He has expressed his continuing sympathies with Orthodoxy in lectures and writings since that time.

Williams has written on the Spanish Roman Catholic mystic, Saint Teresa of Avila. On the death of Pope John Paul II he accepted an invitation to attend his funeral, the first Archbishop of Canterbury to attend a funeral of a Pope since the break under King Henry VIII. He also attended the inauguration of Pope Benedict XVI.

Position on Freemasonry

In a leaked private letter Rowan Williams said that he "had real misgivings about the compatibility of Masonry and Christian profession" and that whilst Bishop of Monmouth he had prevented the appointment of Freemasons to senior positions within his diocese. The leaking of this letter in 2003 caused a controversy, which he sought to defuse by apologising for the distress caused and stating that he did not question "the good faith and generosity of individual Freemasons", not least as his father was a member. However, he also reiterated his concern about Christian ministers adopting "a private system of profession and initiation, involving the taking of oaths of loyalty."[41]

Unity of the Anglican Communion

Williams became Archbishop of Canterbury at a particularly difficult time in the relations of the churches of the Anglican Communion. His predecessor, George Carey, had sought to keep the peace between the theologically conservative primates of the Communion such as Peter Akinola of Nigeria and Drexel Gomez of the West Indies and liberals such as Frank Griswold, the then Primate of the US Episcopal Church and others elsewhere.

In 2003, in an attempt to encourage dialogue, he appointed Archbishop Robin Eames, the Primate of All Ireland, as Chairman of the Lambeth Commission on Communion, to examine the challenges to the unity of the Communion, stemming from the consecration of Gene Robinson as the Bishop of New Hampshire, and the blessing of same-sex unions in the Diocese of New Westminster. (Robinson was in a same-sex relationship.) The Windsor Report, as it was called, was published in October 2004. It recommended solidifying the connection between the churches of the Communion by having each church ratify an "Anglican Covenant" that would commit them to consulting the wider Communion when making major decisions. It also urged those who had contributed to disunity to express their regret.

In November 2005 following a meeting of Anglicans of the 'global south' in Cairo at which Williams had addressed them in conciliatory terms, 12 primates who had been present sent him a letter sharply criticising his leadership ("We are troubled by your reluctance to use your moral authority to challenge the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada"). The letter acknowledged his eloquence but strongly criticised his reluctance to take sides in the communion's theological crisis and urged him to make explicit threats to those more progressive churches. (Questions were later asked about the authority and provenance of the letter as two additional signatories' names had been added although they had left the meeting before it was produced.) Subsequently the Church of Nigeria appointed an American cleric to deal with US/Nigerian church relations, outside the normal channels. Williams expressed his reservations about this to the General Synod.

More recently he established a working party to examine what a 'covenant' between the provinces of the Communion would mean, (in line with the Windsor Report). The strains on the working of the Communion remain evident.

2010 General Synod address

On 9 February 2010, in an address to General Synod, Williams warned that damaging infighting over women bishops and gay priests could result in a permanent split in the Anglican Communion. He stressed that he did not "want or relish" the prospect of division and called on the Church of England and Anglicans worldwide to step back from a "betrayal" of God's mission and to put the work of Christ before schism. But he conceded that, unless Anglicans could find a way to live with their differences over women bishops and homosexual ordination, the Church would change shape and become a multi-tier communion of different levels — a schism in all but name.[42]

Williams also said that "It may be that the covenant creates a situation in which there are different levels of relationship between those claiming the name of Anglican. I don’t at all want or relish this, but suspect that, without a major change of heart all round, it may be an unavoidable aspect of limiting the damage we are already doing to ourselves." In such a structure, some churches would be given full membership of the Anglican Communion, with others on an outside, lower-level track with only observer status on some issues. Williams also used his keynote address to issue a profound apology for the way that he has spoken about "exemplary and sacrificial" gay Anglican priests in the past.[42]

Comments on the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland

Williams said in April 2010 that the child sex abuse scandal in the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland had been a "colossal trauma" for Ireland in particular. He said that "I was speaking to an Irish friend recently who was saying that it's quite difficult in some parts of Ireland to go down the street wearing a clerical collar now."[43] He also said that "an institution so deeply bound into the life of a society suddenly losing all credibility – that's not just a problem for the church, it is a problem for everybody in Ireland." Williams' remarks were condemned by the second most senior Roman Catholic bishop in Ireland, the Archbishop of Dublin, Diarmuid Martin , who said that "Those working for renewal in the Catholic Church in Ireland did not need this comment on this Easter weekend and do not deserve it."[43]

Works

- Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and Fiction (Baylor University Press, 2008); ISBN 1847064256

- Foreword to W. H. Auden in Great Poets of the 20th century series, The Guardian, 12 March 2008.

- Where God Happens: Discovering Christ in One Another (New Seeds, August 14, 2007)

- Wrestling with Angels: Conversations in Modern Theology, ed. Mike Higton (2007 SCM Press) ISBN 0334040957

- Tokens of Trust. An introduction to Christian belief. (2007 Canterbury Press)

- Grace and Necessity: Reflections on Art and Love (2005)

- Why Study the Past? The Quest for the Historical Church (2005 Eerdmans)

- Anglican Identities (2004) ISBN 1-56101-254-8

- Darkness Yielding, co-authored with Jim Cotter, Martyn Percy, Sylvia Sands and W. H. Vanstone (2004) ISBN 1-870652-36-3

- The Dwelling of the Light—Praying with Icons of Christ (2003 Canterbury Press)

- Lost Icons: Essays on Cultural Bereavement (2003 T & T Clark)

- Silence and Honey Cakes: The Wisdom of the Desert (2003) ISBN 0-7459-5170-8

- Faith and Experience in Early Monasticism (2002)

- Ponder These Things: Praying With Icons of the Virgin (Canterbury Press, 2002)

- Writing in the Dust: Reflections on 11 September and Its Aftermath (Hodder and Stoughton, 2002)

- The Poems of Rowan Williams (2002)

- Arius: Heresy and Tradition (2nd ed. 2001) ISBN 0-334-02850-7

- Christ on Trial (2000) ISBN 0-00-710791-9

- On Christian Theology (2000)

- Faith in the University (1989)

- After Silent Centuries (1994)

- Open to Judgement: Sermons and Addresses (Darton, Longman and Todd, 1994)

- Teresa of Avila (1991) ISBN 0-225-66579-4

- Christianity and the Ideal of Detachment (1989)

- Politics and Theological Identity (with David Nicholls) (Jubilee 1984)

- Open to Judgement: Sermons and Addresses (1984)

- Peacemaking Theology (1984)

- The Truce of God (London: Fount, 1983)

- Essays Catholic and Radical (Bowerdean 1983) (ed. with K. Leech)

- Eucharistic Sacrifice: The Roots of a Metaphor (1982 Grove Books)

- Resurrection: Interpreting the Easter Gospel (1982 Darton, Longman and Todd)

- The Wound of Knowledge (1979 Darton, Longman and Todd)

For a detailed bibliography for 1972–2005, see kai euthus.

Honours and awards

- Fellow of the British Academy (FBA), 1990.

- Membership in the Privy Council of the United Kingdom 2002.

- Honorary Doctorates: Univ of Kent, DD, 2003; Univ of Wales, DD, 2003; Evangelisch-Theologische Fakultät, University of Bonn, Dr. theol. honoris causa, 2004; Univ of Oxford DCL, 2005; Univ of Cambridge DD, 2006; Wycliffe College, University of Toronto, DD, 2007; Trinity College, University of Toronto, DD, 2007; Durham University, DD, 2007; St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary, DD, 2010.

- Honorary Student of Christ Church, Oxford.

- Honorary Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford.

- Honorary Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge.

- Honorary Fellow of Christ's College, Cambridge.

- Order of Friendship (Russia), 2010[44]

- Founding Fellow of the Learned Society of Wales (FLSW), 2010.

Styles and titles

- Mr Rowan Williams (1950–1975)

- Dr Rowan Williams (1975–1978)

- The Revd Dr Rowan Williams (1978–1986)

- The Revd Professor Rowan Williams or The Revd Canon Rowan Williams (1986–1991)

- The Rt Revd Dr Rowan Williams or The Rt Revd the Lord Bishop of Monmouth (1991–1999)

- The Most Revd Dr Rowan Williams or The Most Revd (or His Grace) the Lord Archbishop of Wales (1999–2002)

- The Most Revd and Rt Hon Dr Rowan Williams or The Most Revd and Rt Hon (or His Grace) the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury (2002-present)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Church of England — Archbishop of Canterbury

- ↑ "About Oxford, Annual Review". 209.85.129.104. http://209.85.129.104/search?q=cache:2liJ9jyHiJQJ:www.ox.ac.uk/aboutoxford/annualreview/13.shtml+rowan+william+honorary+degree+oxford&hl=nl&gl=nl&ct=clnk&cd=1. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS | Wales | Archbishop becomes druid". BBC News. 2002-08-05. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/2172918.stm. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "About Us". Catching Lives. http://www.catchinglives.org/about-us/. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ http://www.peacemala.org.uk/patrons/rowan.html

- ↑ "The Religion Report: 5 March 2003 - Homosexuality and the churches, pt. 2". Abc.net.au. http://www.abc.net.au/rn/talks/8.30/relrpt/stories/s797569.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "Archbishop's New Statesman magazine interview". The Archbishop of Canterbury. http://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/2065. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ↑ Асланян, Анна (12 November 2008). "Между алгеброй и гармонией" (in Russian). Culture (Bush House, London: BBCRussian.com). http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/russian/entertainment/newsid_7720000/7720087.stm. Retrieved 16 November 2008. "... он [Роуэн Уильямс] овладел русским специально для того, чтобы изучать Достоевского в оригинале."

- ↑ Essays Catholic and Radical (Bowerdean 1983)

- ↑ Politics and Theological Identity (Jubilee 1984)

- ↑ Essays Catholic and Radical, (Ibid.)

- ↑ Grace under Pressure?

- ↑ Terrorists can have serious moral goals, says Williams, telegraph.co.uk 2003-10-15

- ↑ Tales of Canterbury's Future? A terror apologist may soon lead the Church of England., Wall Street Journal, 2002-07-12

- ↑ Sharia law in UK is 'unavoidable', BBC News, 2008-02-07

- ↑ Libby Purves, Sharia in Britain? We think not.., Times Online, 2008-02-07

- ↑ Church in a State - The Archbishop of Canterbury has made a grave mistake, 2008-02-08 Times Online

- ↑ "Archbishop of Canterbury Dr Rowan Williams will visit the Shri Venkateswara (Balaji) temple in Tividale - Birmingham Mail". Birminghammail.net. http://www.birminghammail.net/news/birmingham-news/2008/11/13/archbishop-of-canterbury-dr-rowan-williams-will-visit-the-shri-venkateswara-balaji-temple-in-tividale-97319-22248728/. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Civil and Religious Law in England: a Religious Perspective. Thursday 7 February 2008 http://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/1575

- ↑ Cranmer, Frank (2008). "A Court of Law, Not Morals?". Law & Justice 160: 13–24

- ↑ Cranmer, Frank (2008). "The Archbishop and Sharia". Law & Justice 160: 4

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Judi Bottoni. "Archbishop denies asking for Islamic law". MSN. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23083487.

- ↑ "BBC Interview - Radio 4 World at One". Archbishop of Canterbury. 2008-02-07. http://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/1573. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ "Archbishop slams detention regime". BBC News. 2008-02-21. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/cambridgeshire/7256143.stm. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ "Sharia law 'could have UK role'". BBC News. 2008-07-04. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/7488790.stm. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ↑ "The Body's Grace". Igreens.org.uk. http://www.igreens.org.uk/bodys_grace.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ Mullen, Peter (2004-09-07). "I despair at the 9/11 naivety of Rowan Williams -Times Online". London: Timesonline.co.uk. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,3284-1249948,00.html. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ Stephen Bates, religious affairs correspondent (2006-03-21). "Archbishop: stop teaching creationism". London: Education.guardian.co.uk. http://education.guardian.co.uk/schools/story/0,,1735731,00.html. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ↑ Close (2006-03-21). "Transcript: Rowan Williams interview | World news | guardian.co.uk". London: guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 21 March 2006 09.13 GMT. http://www.guardian.co.uk/religion/Story/0,,1735404,00.html. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ Archbishops slam Iraq jail abuse, BBC News, 2004-06-30

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "BBC NEWS | UK | Archbishop's 'regrets' over Iraq". BBC News. 2006-12-29. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6216099.stm. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS | UK | Archbishop speaks of Iraq damage". BBC News. 2007-10-05. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/7029712.stm. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ Taylor, Ros (2007-09-30). "Bolton calls for bombing of Iran | Politics | guardian.co.uk". London: guardian.co.uk, Sunday 30 September 2007 15.56 BST. http://politics.guardian.co.uk/tory2007/story/0,,2180555,00.html. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ Gledhill, Ruth (2007-10-06). "Archbishop: Iraq far worse than acknowledged -Times Online". London: Timesonline.co.uk. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/faith/article2599716.ece. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ http://www.arabwestreport.info/?q=node/16266 (Arab West Report: art. 38, 52 - 2003)

- ↑ http://www.arabwestreport.info/?q=node/10312 (Arab West Report: Art. 28, Week 31/2005, July 27 - August 02)

- ↑ The Archbishop of Canterbury, Emel magazine

- ↑ US is 'worst' imperialist: archbishop, Times Online, 2007-11-25

- ↑ The Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius website

- ↑ "Rowan Williams apologises to Freemasons". London: Telegraph.co.uk. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2003/04/20/nmason20.xml&sSheet=/news/2003/04/20/ixhome.html. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "Church may split over women bishops and gay priests, warns Rowan Williams", The Times.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 David Batty (2010-04-03). "Archbishop of Canterbury: Irish Catholic church has lost all credibility". London: Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2010/apr/03/archbishop-canterbury-ireland-catholic-credibility. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ↑ "Dr Rowan Williams is honoured for work on Russia". BBC. 12 March 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/8563784.stm. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

External links

- Archbishop of Canterbury official site

- The Anglican Communion's official website

- Canterbury Cathedral official site

- BBC profile

- "The Archbishop's guide to Muslim intolerance" - critical op-ed originally published in Haaretz

- Conservative Evangelical critique of the Archbishop's theology

- Church must be 'safe place' for gay and lesbian people

- 'Early Christianity and Today: Some Shared Questions', lecture for Gresham College in St Paul's Cathedral on 4 June 2008 (available in text, MP3 and MP4 formats).

- Chronology according to Rowan Williams

- Archbishops attack profiteers and 'bank robbers' in City

- Interview of Rowan Williams by James Macintyre during which he spoke about sharia law, capitalism, the disestablishment of the Church, and his love of The West Wing

| Church in Wales titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Royston Wright |

Bishop of Monmouth 1991–2002 |

Succeeded by Dominic Walker |

| Preceded by Alwyn Rice Jones |

Archbishop of Wales 1999–2002 |

Succeeded by Barry Morgan |

| Church of England titles | ||

| Preceded by George Carey |

Archbishop of Canterbury 2002— |

Incumbent |

| Order of precedence in England and Wales | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Harewood |

Gentlemen as Archbishop of Canterbury |

Succeeded by The Rt Hon Kenneth Clarke QC MP as Lord Chancellor |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||